Jiří Smíchovský

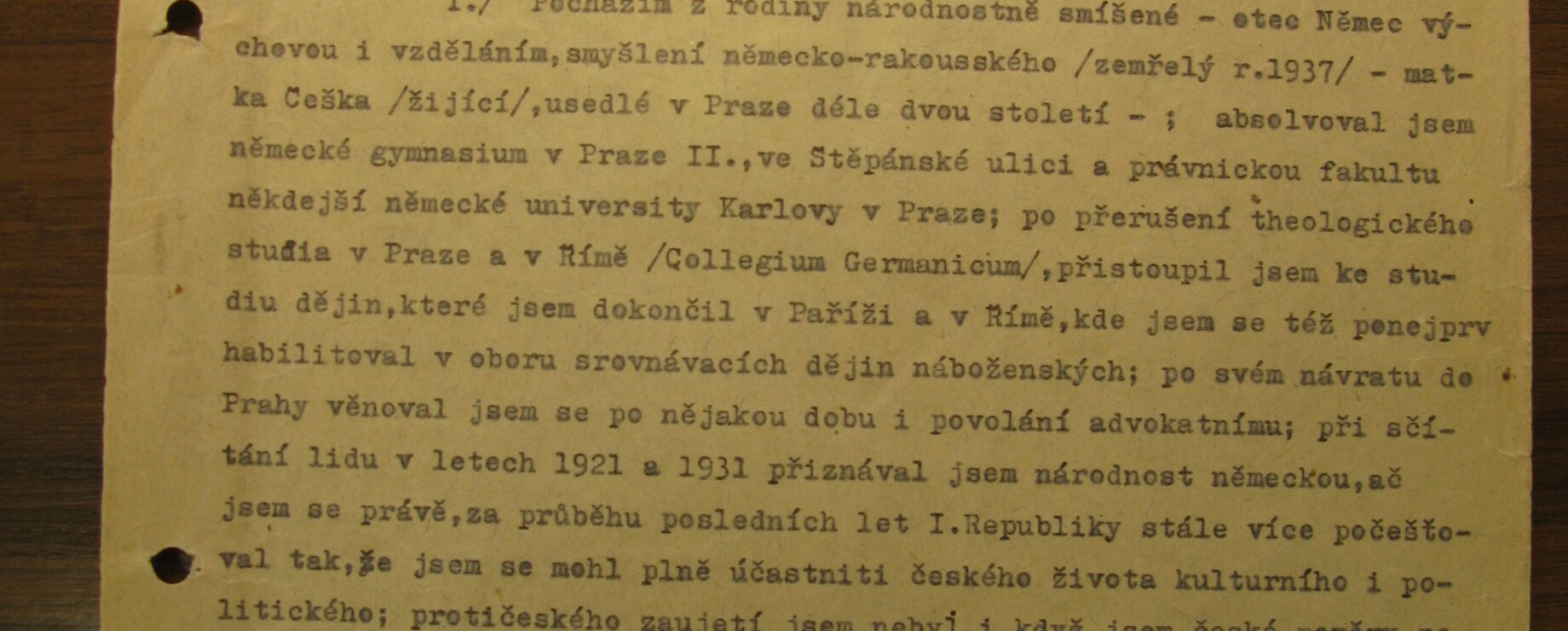

Jiří Smíchovský was a Prague native. He was born to 1989 to a prominent, longstanding family in the city. His father owned a printing business, but Smíchovský had other career plans. In 1916 he matriculated into the German University of Prague. Shortly thereafter Smíchovský was drafted into the Habsburg army, and in 1918 he was captured by the Italians while fighting in Albania. In the decade following the war, Smíchovský testified in his deposition, he completed his degree in law at the German University; obtained advanced degrees in theology in Prague and at the Collegium Germanicum in Rome; and studied history in Paris and then Rome, where he habilitoval. He returned to Prague in 1929, where, he claimed in his deposition “věnoval jsem se po nějakou dobu i povolání advokatnímu.”

Smíchovský’s work as a lawyer was, however, just a cover. Shortly after his capture by the Italians, he received training in zpravodajský and worked for the Italian intelligence service throughout the interwar period. Upon his return to Prague, he joined numerous organizations and a wide range of political parties – National Socialists; Social Democrats; Lidovou stranu; and Fascists – with the purpose of gathering information that he then reported to the Italian embassy. Shortly after the occupation, Sicherheitsdienst agents arrested Smíchovský. He claimed that he was then coerced into becoming an informant. The head of Prague’s branch of the Sicherheitsdienst, however, denied this claim, arguing that in the early months of the occupation the organization only took on volunteers. Whatever the case, Smíchovský clearly took pride in his work, a pride that emanates throughout his deposition, even as he sought to distance himself from Nazism’s crimes. Indeed, as the court wrote, Smíchovský “sám doznává, že již ve svém mládí jako středoškolský student byl zpravodajsky činným.”

Smíchovský was a spy, but the court also took great pains to understand his character, to understand what led the man to become one of the Sicherheitdienst’s most notorious informants and agents provocateurs. The verdict, for example, took particular pains to point out that Smíchovský “sám střídal svoji národnost podle okolností,” which, for the court and many Czechs in the postwar period, suggested a lack of moral fiber. Smíchovský, the court wrote, had claimed Czech nationality in the censuses after 1921 but became a Reich German citizen in 1939. (In his deposition Smíchovský wrote, in Czech, that he had claimed German nationality after 1918 but had taken part in Czech cultural and political life.) For many Czechs during and after the occupation, so-called amphibians represented a failure to stand for something, a failure to act nationally when the very existence of the nation had been threatened. In some cases, such as Smíchovský’s, they utilized their in-between status for personal gain during the occupation.

Thus, many reputed Czechs who obtained Reich German citizenship during the occupation – roughly 300,000 according to the Czechoslovak Ministry of Interior – were tried for “offenses against the nation” after the war as part of a larger effort to “cleanse” the postwar nation. Smíchovský, the court decided, was more than just an amphibian, however. He was “chladnokrevný” and “cynický”. His efforts were marked by “abnormalní intelektuální schopnost”. One witness called Smíchovský a psychopath who lacked any sort of concern for others. Another testified that he “wanted to do something big” and enjoyed wielding power over others. Thus, court documents paint a picture of a professional spy who saw those around him as objects in a game that he sought manipulate, a game that gave him a sense of cold self-satisfaction. He was anational in an age of nationalism, apolitical in an age of extreme politics. Or so it would seem. Was this all to the man? Click on the links to the right or the spots marked on the map to learn more about Smichovský, collaborations, and the Nazi apparatus of terror during the occupation.

Foto: Hlášení Sicherdienstheit, zdroj: Archiv bezpečnostních složek.

Další místa na téma "Collaboration"