Collaboration

Before the Nazi occupation of Prague and the establishment of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, the term "collaboration" was synonymous with "joint work" or "cooperation". Over the next few years, however, the word took on a second, somewhat more sinister meaning, a concise definition of which can be found in one of the post-war dictionaries: 'dishonest cooperation (especially political) with the ruling enemy, in our case especially with the Nazi occupiers'. Similar etymological changes can be observed throughout the continent, as trials of collaborating compatriots and identification of the accused for post-war retributive trials took place in almost all European countries. After all, Edvard Beneš had already declared in a radio address in February 1945 that Czechoslovakia would "carry out the cleansing of the republic of fascism, Nazism and collaborationism as is done in all liberated states".

The Nazi government was completely dependent on the cooperation of the citizens of the occupied countries, especially in highly industrialised areas considered Lebensraum, such as the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. In their efforts, however, the Nazi rulers were remarkably successful despite the heroic deeds of resistance groups. Many Czech leaders from the Second Republic retained positions in the Protectorate government. Only ten thousand Germans supervised the 400,000 Czech civil servants employed in the civil service. Journalists published propaganda articles in Czech newspapers. Workers produced weapons for the Wehrmacht. Tens of thousands of Czechs denounced their countrymen to the Gestapo.

But is it even possible to consider all of this a "collaboration"? The above definition fails to distinguish between different types of collaboration. Although the term "collaboration" at its core conveys not only action but also moral condemnation, this definition fails to reveal the motives and intentions of the collaborators. Is there no difference between the active and enthusiastic collaboration of Emanuel Moravec and the reluctant, essentially tragic collaboration of Emil Hácha? Or between a worker who was merely loafing at work and a worker who joined the resistance? Why were some workers forced to choose to stay on the job and thus avoid certain imprisonment and death, while others were not? What led people to denounce and destroy the lives of their neighbors, friends, or relatives?

Although the retributive courts faced exactly the same questions after the war, this ambiguity raises further questions, the answers to which would perhaps help us to better understand this terrifying period of Prague's history. What choices did the people who lived in the Protectorate have? Why did they behave the way they did under Nazi rule? What were the consequences? Why did some of them actively support the regime? What did they think they would gain and what did they achieve?

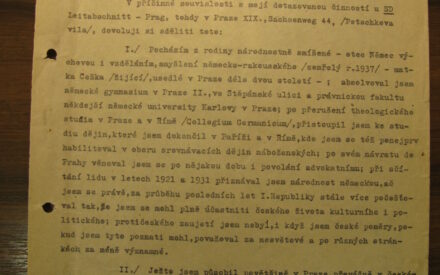

In this text, we try to trace the activities of Jiří Arvéd Smíchovský, a Czech and German-speaking Prague resident who became one of the most famous Sicherheitsdienst agents in his home town shortly after the Nazi occupation. What led the highly educated World War I veteran Smíchovský to join the Sicherheitsdienst? Who did he betray and betray and with what intent? In the following pages we will also look at Smíchovský's role in espionage and Protectorate repression. Through Smíchovsky, much can be learned about the confused and chaotic beginnings of the Nazi reign of terror and why it was so successful. Smíchovský also reveals why whistleblowing and espionage played a key role in the liquidation of Prague's Jews. The post-war retributive court sentenced Smíchovský to life imprisonment in 1947. It is the documents produced during this trial that allow us to trace his activities and to investigate his motives.

Author of czech text is historian Chad Bryant.

See also

SoPaDe

German Social Democracy in Exile in Czechoslovakia.

Notable Women of German-Speaking Prague

The theme maps important places connected with the history of women's emancipation with a focus on the German minority living in Czechoslovakia in the interwar period.

A literary walk through Kafka’s Prague on the trail of his story Description of a Struggle

Procházka sleduje cestu, která je vylíčena v Kafkově dílku z let 1904–1910 Popis jednoho zápasu.