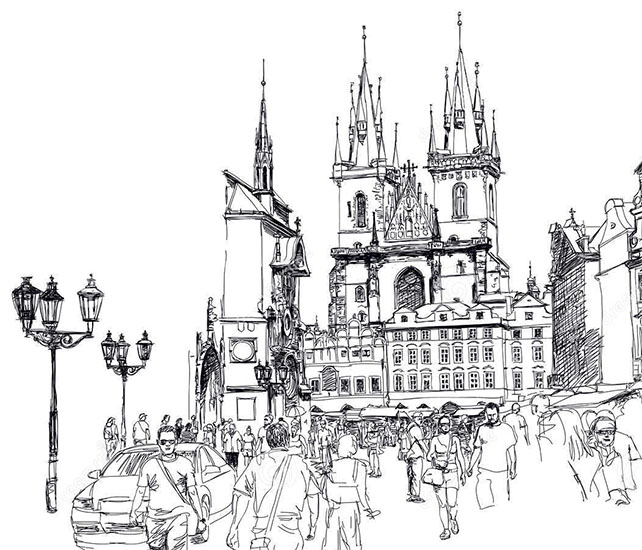

Na Příkopě

This building had been home to Elekrafilm, a highly respected distribution company that was Aryanized after its owner, Josef Auerbach, fled the country in 1939. Soon thereafter the building became home to Árijský boj, a hate-filled propaganda newssheet modeled after Julius Streicher’s Der Stürmer. Árijský boj was noted for its support of Nazism as well as its anti-Beneš, anti-First Republic rants, but it focused, not surprisingly, on cultivating anti-Semitism among the Czech reading public. It also played a key role in the Nazi suppression and murder of the Jews.

As Benjamin Frommer writes in Národní očista. Retribuce v poválečném Československu, Árijský boj actively cultivated denunciations from its readership. Indeed, the paper received about sixty letters a day condemning others of anti-Reich activities. Early in the occupation, many of these letters targeted Jews who had transgressed regulations limiting access to public spaces or restricting times when they could shop for food. Czechs condemned fellow Czechs for fraternizing with Jews. Much of this information was then passed on to the Gestapo and the Sicherheitsdienst.

In his postwar trial, Rudolf Novák, editor-in-chief for Árijský boj, testified that Smíchovský and fascist leader Rudolf Gajda’s chauffeur read through the letters for the Sicherheitsdienst. (Eventually this became the full-time job for another agent,) Smíchovský, Novák testified, had even travelled to Nuremberg, where he successful gained the financial support of Streicher’s Anti-Jewish League. Why the initiative? Karl Herman Frank and others, Novák testified, had become suspicious of the paper. Did Smíchovský argue on behalf of Árijský boj’s “success” —and thus his own success — as a means of gathering intelligence? Was he driven by anti-Semitism? Or perhaps was he seeking to protect his comrade Maximillian Passer, the paper’s major financial backer? Smíchovský makes no mention of his work for Árijský boj in his testimony.

Árijský boj and Smíchovský also played a key role in the registration and marking of the Protectorate’s Jews. Beginning in 1940, all Jews, as defined by the Nuremberg Laws, were required to register with the Prague Jewish Community. The regime stamped their identity cards with a “J” and took note of the address. They used information gathered during the registration process to seek out family members. In 1941, using lists gathered during the registration process, the SS and its minions began the mass deportations Jews, a journey that led to the death of more than 78,000 men and women whose last names fill the walls of the Pinkas synagogue. Only precious few Protectorate Jews managed escape registration and survive the occupation in hiding.

Árijský boj encouraged Czechs to denounce Jews who did not register. It also published the names of Jews who had not registered, and encouraged their readers to seek them out. Meanwhile, Adolf Eichmann’s Office of Jewish Emigration had tasked Smíchovský with helping to determine who was a Jew, or a Mischlinge. Smíchovský thus conducted extensive genealogical work in Jewish registries as well as Jewish archives while, on the side, writing long pieces for the Sicherheitsdienst on Czech-Jewish relations. In his deposition Smíchovský claimed that he did not want to harm Jews, and in fact got along better with them than Czechs. He could not resist boasting about his ability to read Hebrew fluently.

Foto: Ulice Na Příkopě 7.1. 1945, source: archiv ČTK/autor unknown.

Další místa na téma "Collaboration"