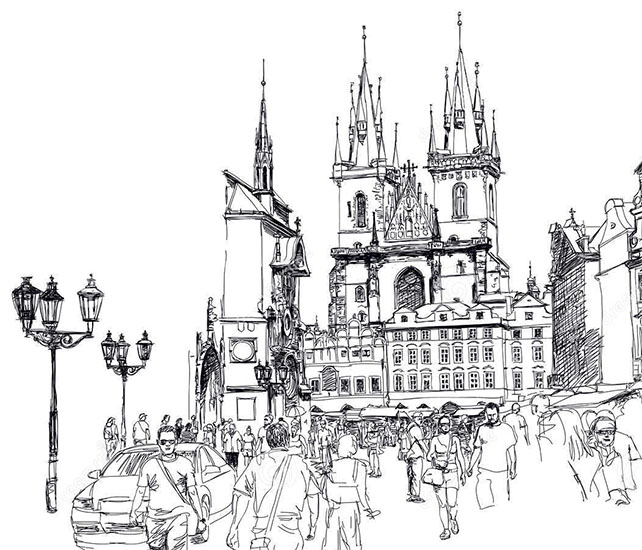

U Medvídků

During the occupation U Medvídků was a vinárna U Petříků, named after its owner, and had been a favorite hangout for Jiří Smíchovský and his occultist friends. One evening – the date is not revealed in the court documents – Smíchovský was here having a drink with his fiancé, Naděžda Nikolajevna Ragozina-Jastrebová, a Russian émigré, doctor of philosophy, and university librarian. Smíchovský and his fiancé were speaking loudly in German. Mr. Petřík informed them that they should speak Czech in his vinárna, and that they had been acting rudely. Four days later the Gestapo arrested Petřík. He apparently perished in Mauthausen shortly thereafter.

An employee of the vinárna and three others testified to the court about the incident, which formed the basis of the court’s final verdict. In its final judgement, the court described in detail Smíchovský’s various activities on the part of the Sicherheitsdienst, including his role in the roundup of Prague’s occult community. Yet, it claimed, the court lacked direct evidence of denunciation, or any other act that had led directly to someone’s death – with exception of Petřík.

Smíchovský was thus sentenced to life in prison, which he served in Mírov until his death in 1951. One wonders, however, if a plea bargain had been struck. Smíchovský acted as a key witness against dozens of Czechs and Germans after the war and provided detailed information about the Sicherheitsdienst and other organizations that allowed prosecutors to reconstruct these institutions’ organization and membership. Not surprisingly, perhaps, Smíchovský became an informant for the StB while in prison, and supposedly lived in conditions superior to his other cellmates.

The court also drew upon witness testimony and court documents to argue that Smíchovský nothing more than a spy, an amphibian, an opportunist, and psychopath. But is that the complete picture? We might complicate the story a bit. Smíchovský’s fiancé was arrested by the NKVD shortly after the war, yet he appears to have tried to protect his three closest occultist friends whom he often met at U Petříků. In his deposition, Smíchovský made excuses for a certain de la Camera’s collaborationist activities and did not denounce two other close friends, N. A. Muchin and František Kabelák, both of whom survived the war. Did Smíchovský feel a certain loyalty to them? Did they share a vision of the occult that might have justified Smíchovský’s actions, a vision that allowed him to feel superior to the world around him, a vision that promised a perverse escape from the madness around him? Probably not, but we’ll probably never know.

Další místa na téma "Collaboration"