Former Hotel “ Zur alten Post“

(The Old Post Office)

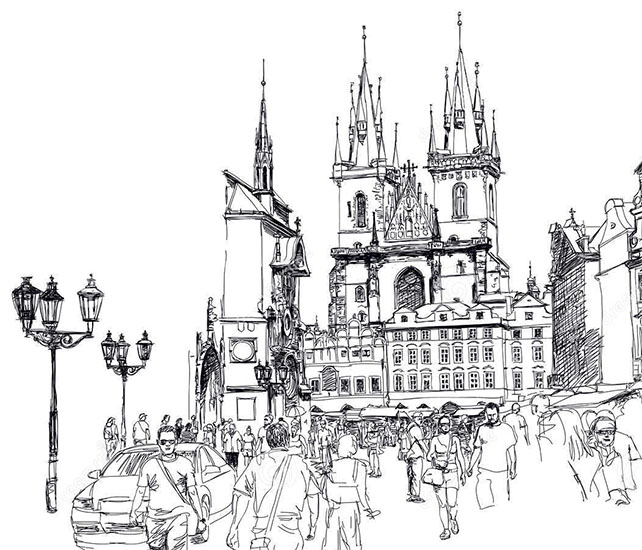

And from his hiding place Jarda notices how the girls disappear into the “Old Post Office“, whose façade is partly hidden by the statue of Jan Nepomuk, made by Ferdinand Maxmilian Brokoff in 1715. As the main Prague post office of the Habsburg monarchy, in the eighteenth century the building‘s façade was painted an imperial yellow, which is the shade that has been preserved to this day. Before the First World War it was home to a well-known bordello.

Egon Erwin Kisch: The Pimp (from page 31 on)

At home Jarda would not eat even the tiniest morsel. His mother becomes suspicious of Jarda‘s behaviour and she asks what has happened to him. He explains that he only has a slight headache. But his mother is not to be fooled, she is horrified at the boy’s appearance, as he looks as if he had been pulled out straight from the River Vltava. “This afternoon we’ll go together to the doctor.“

“I’m not going anywhere.“ He runs out. Where to no-one knows. By four o’clock he is hiding on the corner of Hroznová Street where he waits till Betty comes. She does not spot him.

Later he runs towards the little bridge by the mill, which crosses the Čertovka, and follows her with his eyes until she meets up with Emy. From there he rushes through the Old Baths (Staré lázně) and watches from behind the corner as Emy and Betty go in through the hotel gate and disappear.

Now he slips in to the entrance in front of the Maltese church. Jarda knows it well here, as the students from the German Realschule in Kampa come here to worship. He stands behind the pillar in order to see the hotel directly. His view is not even obscured by the brown statue of Saint John in the square, on whose pedestal hangs a dried-up wreath and a light from a lantern is flashing red. The hotel’s windows are all wide open. Curtains hang in the windows, their two halves are joined only at the top with the rest left hanging pointing down towards both corners of the windows, thus leaving an uncovered space the shape of a triangle. From below, however, Jarda cannot pick up anything from the darkened interior, therefore he wouldn’t know which room Betty and the man are in.

And all of a sudden – Jarda cannot even let out his breath – a man with a brown goatee beard comes to a window on the first floor. He pulls the cord of the roller blind. Slowly the yellow cloth curtain slides down to the window sill. It hides the man, hides everything… Only a yellow net curtain with red stripes along the edges remains to be seen in the window.

Jarda feels somewhat queezy, so he has to lean against the pillar. His gaze is obscured by that yellow curtain with the red stripes, but his stare penetrates it, behind it he espies that fellow with the goatee beard holding a hundred-crown note in his hands, kicking out at Betty while she is kissing his feet, she must kiss his feet, he is denigrating Betty and roaring with laughter. And then Jarda’s eyesight fails. The statue of the saint with the dried-up wreath on its pedestal disappears, the red light in the lamp disappears, the lamp itself and everything else all disappear.

He staggers out from there. Above the windows of Buquoy Palace a host of apparitions all with goatee beards are grinning broadly from the walls, one like the next, and all of them are pulling down the blinds.

Jarda’s tears well up in his eyes and he bursts into a bitter crying fit. An astringent taste spreads upon his tongue. It tasted like the candied calamus that he once bought from the vendor of sweets in the belief that it was orange peel.

He feels a dryness in his throat. A void in his stomach. In his eyes he feels pain from crying. His heart pounds alarmingly. His forehead glows red-hot, well, not quite, it is rather cold. Thoughts hack into his suffering, thoughts that hurt to the very depths of his soul.

He would like to feel comforted in some way and so he is pondering: after all, that unknown chap is alright, he has to fork out a hundred for it.

But all of a sudden, though, a horrifying thought strikes him: he only gives the girl one hundred crowns if it’s the first time – so now she’s lost her worth. She’s lost her worth.

Jarda pulls himself together and he is possessed by the idea of running after Betty to the Post Office Hotel and warning her, quickly, before it’s too late. But he can’t do it. His stomach is churning and little Jarda throws up. Mucous, greenish pieces of bile gush into the Vltava River. Everything is spinning round with him, he himself damn near fell into the water, he only just caught himself.

He has a feeling as if somebody is standing up above on the bridge, is leaning against the rail and following what is happening to him. He looks up. There’s no-one there, only the statues of saints, with their backs turned to him. As if they were half-rounded, polished columns. The lighter coloured areas are showing the places where repairs have been carried out and these are visibly in contrast with the original dark stone. The workers did not even attempt to hide the difference. Why bother anyway? They are hidden at the back, so it does not matter, since the passers by walking past them look at the statues only from the front and the rear side of them, which are not exactly pretty, go unnoticed. People haven’t got a clue about anything. They have no idea what goes on in the Post Office Hotel. Otherwise they would not be strolling so calmly here.

With the passing of time Jarda becomes the girls‘ pimp, who, like an all-powerful master over the fate of his women, acts completely heartlessly, finally contracting a sexually-transmitted disease and coming into conflict with the law. Later, after he finds himself more and more excluded from society, and with only one of his girls remaining – a girl whom he treats with affection and whom he wishes to marry. However, he does not have the money to realise this decision, so he decides to steal from his father, but the housekeeper walks in on him and Jarda hangs himself.

This guided walk is a part of the “Democracy on the Brink. Historical lessons from the late 1930s” project supported by the Europe for Citizens programme of the European Union.

Další místa na téma "A literary walk through Kafka’s Prague on the trail of his story Description of a Struggle"